The flavor and texture of cooked Apios is not like a potato, and many folks get disappointed that it’s not a stand in for potatoes. Apios tubers have a much higher protein content (about threefold), and a flavor which, to me, is more reminiscent of Black-eyed Peas.

One can make delicious, crispy-fried chips from thinly-sliced tubers. I shredded some Apios tubers and formed patties, rather like latkes. No egg was added, yet they held together just fine. The flavor was excellent and they stayed crunchy on the outside, soft on the inside.

I mashed boiled Apios with Maple Syrup and a bit of butter and then gently fried it to create a dish which was remarkably like peanut brittle. Very little is published as far as recipes, so I’m working on some.

Boiled, they can get gummy, which is more pronounced as they cool off. This thickening is quite handy when making a bisque or thick stew. I always peel mine, which is where the domesticated types come in. It’s far easier to peel larger tubers. The tubers exude a sticky white sap, so having cold water to rinse it off before it dries is wise. Do not consume Apios tubers raw.

Wild Apios typically make small tubers, dime to quarter sized. Even these may take a couple years to form. The original “mother” tuber continues to gain size, but I’m not sure at what point its culinary value goes downhill. One to two year tubers are fine, but digging quarter-sized tubers in something more suited for wild food foragers, which I’ve done many times.

From 1985–1994 the LSU team, headed by Dr. Wm. Blackmon and Dr. Berthal Reynolds collected, bred and selected for larger tubers and better yields. Apios tubers went from nickel to quarter sized (1 year old) to the size of medium potatoes in a single season. This was a huge leap forward in Apios domestication. While the program has since been dropped by LSU, a group of growers and nurseries maintain much of the LSU strains and Bill Blackmon continued his plant breeding at his property in Virginia. I have recently heard from Bill that he’s decreasing his efforts with Apios, which is a well deserved rest from a remarkable life’s work.

It is hoped that future breeders will shape Apios domestication to solve some issues which make the crop challenging on a large scale. One of the biggest issues is the tubers often stray far from where they were planted. runners can get 3 feet or more from the mother tuber, making harvesting more difficult. One of the goals is to get shorter stolons, so tubers cluster under the original planting. This has been dome with other crops, like Jerusalem Artichoke, Helianthus tuberosus.

I have seed from wild Apios, collected in Virginia, which may hold promise in this direction. When I worked at the Center for Historic Plants, at Monticello, some gardeners came and asked me what the “weed” was which they had been sent to remove from an Azalea planting. When I saw it was Apios smothering the Azaleas, I dug down and found some very large tubers, which I collected. Seeds from the plants was also secured.

What was also interesting: amongst the Apios tubers, there appeared to be quartz shards, from tool or arrowhead making. Had Native Americans planted these, many years ago? Who knows. What is known is that the aboriginals used Apios extensively and traded them as a food article.

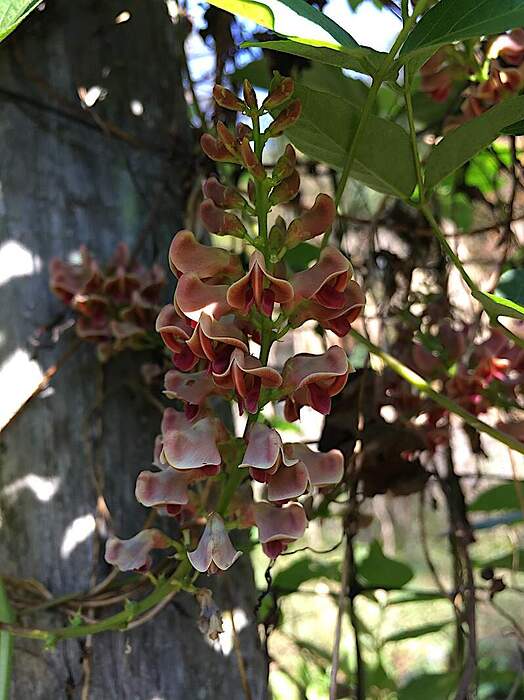

The rambling vines produce best if trellised. I’m wondering if they would produce well if planted on the south, sun-facing side of a corn field. It’s also possible that a sturdy variety of corn, such as Hickory King, could be planted a bit farther apart (for increased sun penetration) and used as trellising for the vines.

More, when time permits.